ArtsEtc Inc. 1814-6139

All works copyrighted and may not be reproduced without permission. ©2013 - hoc anno | www.artsetcbarbados.com

All works copyrighted and may not be reproduced without permission. ©2013 - hoc anno | www.artsetcbarbados.com

WE HAD a close encounter in our house a couple months back. It was unplanned, unexpected and poetic in nature.

With that casual, don’t-carish air teenagers practice so well, my daughter picked up the review copy of Kamau Brathwaite’s Liviticus, published by House of Nehesi, that has occupied space in our front-house for a while now (along with overdue library books and other unfinished titles) and read the whole thing—thirty pages—out loud, including earthy, elegant foreword by Garrett Hongo and the author’s bio at the end.

It was, in and of itself, a warm, reaffirming, mother-child bonding, magic-blanket of a moment. A rare treat for me as someone who loves to be read to but is nearly always the reader. It was certainly one for the treasured memory chest, to be tissue-paper-wrapped, taken out only occasionally and with care, to prevent it from fraying—and I can see it already—through overhandling.

Beyond that, it was a prime learning moment, with poetry as the teacher.

First, I learned about my daughter. It was a joy to observe her while she read aloud to me; to see her pause and smile—or stumble and frown—at a particular reference or turn of phrase; to watch her face reflect recognition, understanding or questioning. She was already familiar with Kamau’s poetry, having studied some of it for CSEC (Caribbean Secondary Examination Certificate). Wasn’t scared of it! Had worked out that you need to be alert, engaged and paying attention when considering the man’s writing. She had told me this some time ago, but it was fascinating to see the live, practical application on this particular evening.

But what made my daughter pick up any book of poetry outside of a school setting in the first place?

The art student in her had been admiring Liviticus’ glossy cover in passing, the reproduction of Fay Helfer’s original portrait on wood of the author attracting her in particular. The book’s roughly A4 format and interior design with generous white space reminded her, she said, of a graphic novel or comic book. It was just asking to be picked up! Adding to the graphic-novel quality were the photographic images illustrating three of the poems, plus a contents page and segment numbering/titling that were an adventure in graphic design itself.

And what struck her while reading, and me while listening?

Between us, we listed playfulness of language even in the midst of sorrowful and harrowing themes; twists or layers of meaning uncovered by that wordplay; Kamau’s delving into themes of slavery, colonization—of holocaust—that she is now studying for CAPE (Caribbean Advanced Proficiency Examination); his subtle dwelling on the colour blue; his references to social media—the Facebook “Like” turned sharply in on itself. Kamau deploys his Sycorax Video Style (SVS) in such a way that his often challenging, highly visual font and typeface—even in the midst of mourning, warning, and complaint (and there is plenty in Liviticus)—also conveys beauty, love and generosity. Maybe even hope.

Reader take care? "Liviticus is perfomed in the author's camera-ready Sycorax Video Style [SVS]."

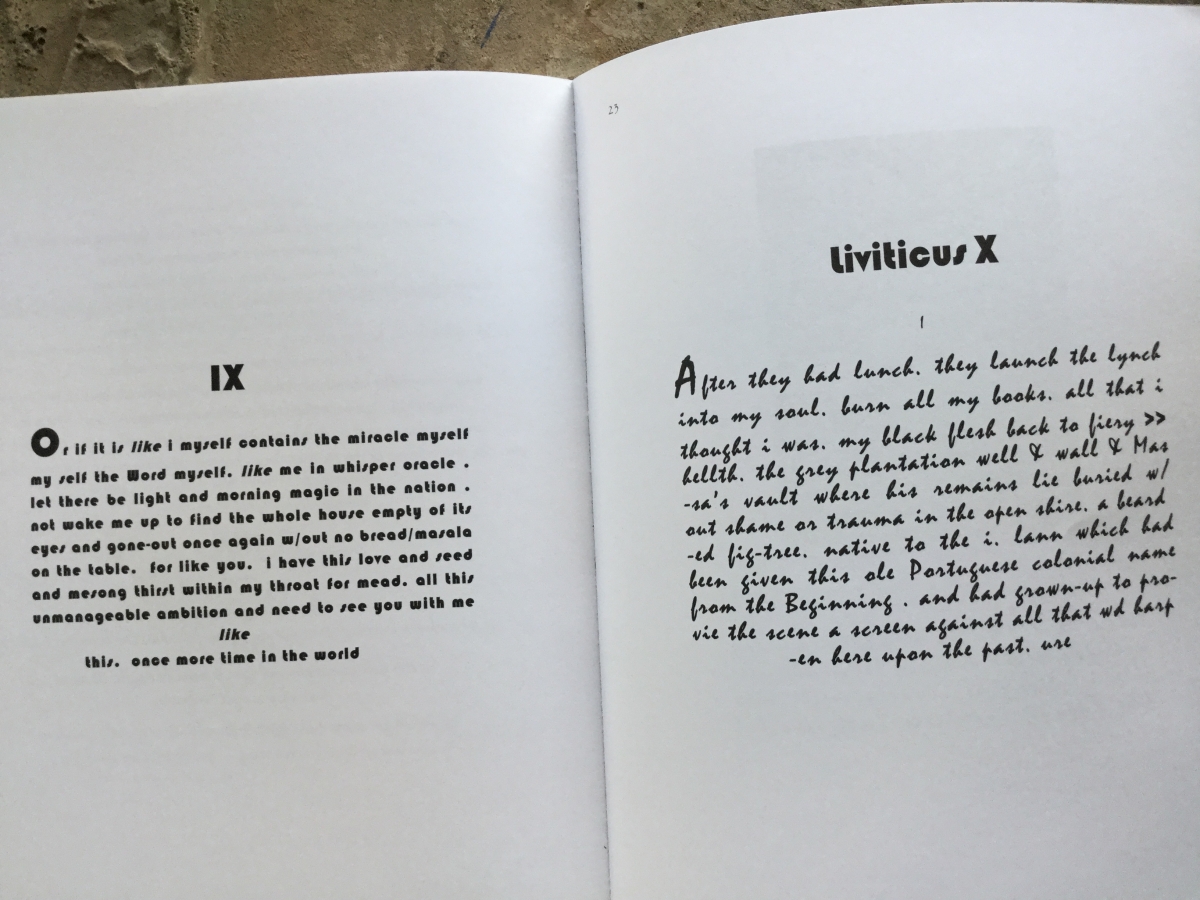

Two sections near the end of the collection entitled IX and Liviticus X illustrate some of our list. Some of the most challenging uses of SVS are found in these sequences, which deal pointedly with personal/cultural lynching: the loss of land, of books, property, erosion of health, comforts, peace of mind. This part of the lament is told in formidable chunks of justified Bauhaus and Mistral—the block font and emboldened cursive script, respectively, varying in point size; the lines punctured with idiosyncratic breaks and punctuation.

On page 22, for instance, the font leaves the reader no choice but to shift gears to navigate the distress of “wak[ing] up to find the whole house empty of its eyes…w/out no bread/masala on the table.” No choice on page 25 but to take time to trace the tracks of the “likkle yellow bob-cat” that comes “like a stealthy submarine” to cut down ancestral tree, dreams, history.

Lighter, more standard and playful fonts are used, too. Elsewhere, in the segment entitled "At Bedward Chapel,” a distinctly party style is chosen—its exaggerated curlicues and serifs somehow effective in evoking the decidedly unparty-like feel of ancient ritual, and “cyandles” curling and flickering in a ruined chapel at midnight.

But mother and daughter are in agreement that the more personally wrenching the subject or lament, the more challenging the typeface.

The reader is “invited” to slow down, to take time to ingest and digest what is being told—akin to being challenged to listen closely—to feel uncomfortable, to be there in the moment of personal sufferation with the poet. Kamau’s poetry makes demands of its audience, as we mentioned before. It can be hard work, but there are rewards.

Some of those rewards counter-threading the difficult text are moments of sheer light and delight and reveal the wordsmith hard at play. In the same segment that describes house and table bare, for instance, we come across the appeal:

“I have this love and seed and mesong thirst within my throat for mead.”

We cannot help but pause in our acknowledgement of heartfelt plea to repeat the line, to twirl it around the tongue, once, twice, three times before continuing. Likewise:

“After they had lunch, they launch the lynch into my soul” and “we have become poorer and poorer like when we was poured out of Africa….”

Other rewards take shape as guest appearances or “features” as if on a hip hop album: a musical invocation of Guyanese poet Grace Nichols in her English garden and the encompassing of fellow Barbadian writer Margaret Gill’s own wry, joyous wordplay “Myrrh” evoke an image of poets hearing each other’s cry and reaching out, physically or mentally, with comfort and balm at the precise and needful moment.

The colour blue also makes guest appearances, along with other colours, daubing itself here and there. The attentive reader is rewarded with splashes of it in “woo-doves and young blue pigeons”; a blue lamp burning by a lonely bedside; and “lilacs…and blue pin-cushion periwinkle,” all of them arrowing at things lost, solitude, and hauntings.

*

“NOW IT IS TIME for the burning of the body and the teefin of the books…” begins section VI, The Lynching.

Here is lamentation, in just twenty-nine lines over two pages, of our history, the legacy of slavery, our own social and cultural loss as African peoples, our own lynching by ourselves and others; a lamentation of how quickly we have forgotten, are forgetting. Kamau likens that neglected history and existence to an “ole house in a forest” that the bees have left to decay and eventually to fall. He further laments our “blind blood knocking at the darken door” and gives thanks that his eyes can’t see anymore “the inconsolable loss.”

A “monument to sorrow” is how Hongo describes these poems in his foreword. Liviticus is indeed this, a searing account of a cultural and public, private and personal lynching. It is also a complaint. A beautifully and skillfully crafted moan.

Ah cyhan complain, we often tell ourselves and others as we go about our daily lives and routines, wuh good it gine do? But Kamau goes ahead, gets it all off his chest about his circumstances, his fate, health, his land, his culture, his history, his fellow beings, those who have ignored, forgotten, encroached, destroyed. Perpetrators and bystanders. He unburdens.

Readers might be left with a sense of being grumbled at, chided, forcefully reminded—lest they forget. But beyond the complaint, we are being strongly cautioned. Liviticus is a very real call to, or for, action, the poet presenting if not with a how-to, then at least with a why-to.

The Old Testament Book of Leviticus, believed to have been written by priests, is presented as a warning and as a set of instructions for the way man should live via belief system. The Greek word Levi means priest. The title of Kamau’s Liviticus, with its slightly altered, offset spelling, can be seen as more than just further evidence of the poet’s penchant for wordplay. Take into account the section entitled “Obatalà,” with its accompanying photograph of four Yoruba priests, and we cannot help but make the connection: these poems are a warning, an instruction from an elder with hindsight, farsight and insight, as a way for us to live.

Liviticus, then, can be taken as an instruction manual, a beautifully presented one that comes with a tick-tick-ticking sound and feel to it. The ticking suggestive of history, memory, time slipping away; or of incendiary device. Of precious loss either way, historically, impending and in real time, even as the words themselves are being written/spoken/absorbed.

*

AS CHALLENGING as the subject matter and delivery are, this is a slim volume that can be read in one sitting—our close encounter with Liviticus lasted an hour, maybe. Rereading is another matter entirely, however, for while these poems may not be long, they are like oceans.

So, what else did I learn?

That you can complain if you want to. Just make it beautiful, make it sing, and make it stand for something beyond the complaint. Examples elsewhere in the popular culture might include the Mighty Gabby’s “Emmerton,” Bob Marley’s “Ambush in the Night.”

That there are ways to make poetry, even difficult poetry, accessible and shareable without resorting to the watering down currently trending in “Instagram poetry” and the like. You do not have to sacrifice language, originality, true depth of feeling or expression—to reach your audience. For me, there is a neat tie-in to the section entitled “facebook,” in which Kamau teases us with the idea of exchanging the social media like for some deeper consideration, such as know.

Finally, I was also reminded, in case I’d momentarily forgotten, that Poetry is pure alchemy.

It transforms us into gentler beasts for a while. Envelopes us and has the power to hold and comfort us. Can make us think and act differently. Can temper teenageritis. Can substitute for a glass of wine at the end of a tiring or frustrating day. Can substitute for prayer. Can spur a reviewer closer to her deadline.

Poetry brings people together, and we should all be reading it—to ourselves, to others, out loud, in a crowd. In fact, there ought to be a law about it that brings us, to borrow from page 20 of Kamau’s instruction manual, “into the curl” of verse.

Last updated December 12, 2018.